Reckoning: Family Businesses Confront Race, Racism and Inclusion

Business families are educating themselves about the Black-white wealth gap in the United States and discussing what they can do about it.

Shirley Plantation, founded in 1613, is America’s second oldest continuously operated family business. As you might expect from its age and name, the Charles City, Va., property once relied on the labor of enslaved people.

Photo courtesy of Shirley Plantation.

What you might not expect is a statement on the plantation’s website that acknowledges the founding family’s role in enslavement and condemns the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police on May 25, 2020. “We are committed to making real and lasting change, and will use our history to educate and advocate for real progress and equality,” says the statement, which is signed by Charles Carter, 11th-generation descendant of the founders, and his wife, Lauren.

No enterprising family that we’ve worked with isn’t wrestling with these issues in some way.

“We face a lot of assumptions about our family,” Lauren says. “We wanted to squash those and speak out to do our part in creating positive change and healing.”

Today, Shirley Plantation is a tourist site, owned by a foundation the family formed in 2010. The Carters also farm a small portion of the land and rent the rest to other farmers.

Floyd’s killing sparked what journalists and other observers have called a new civil rights movement. Like the Carters, other white American family business shareholders and stakeholders have been discussing how to meet the moment.

“No enterprising family that we’ve worked with isn’t wrestling with these issues in some way,” says Ashley Blanchard, philanthropy practice leader and a consultant at Lansberg Gersick & Associates, a family business advisory firm.

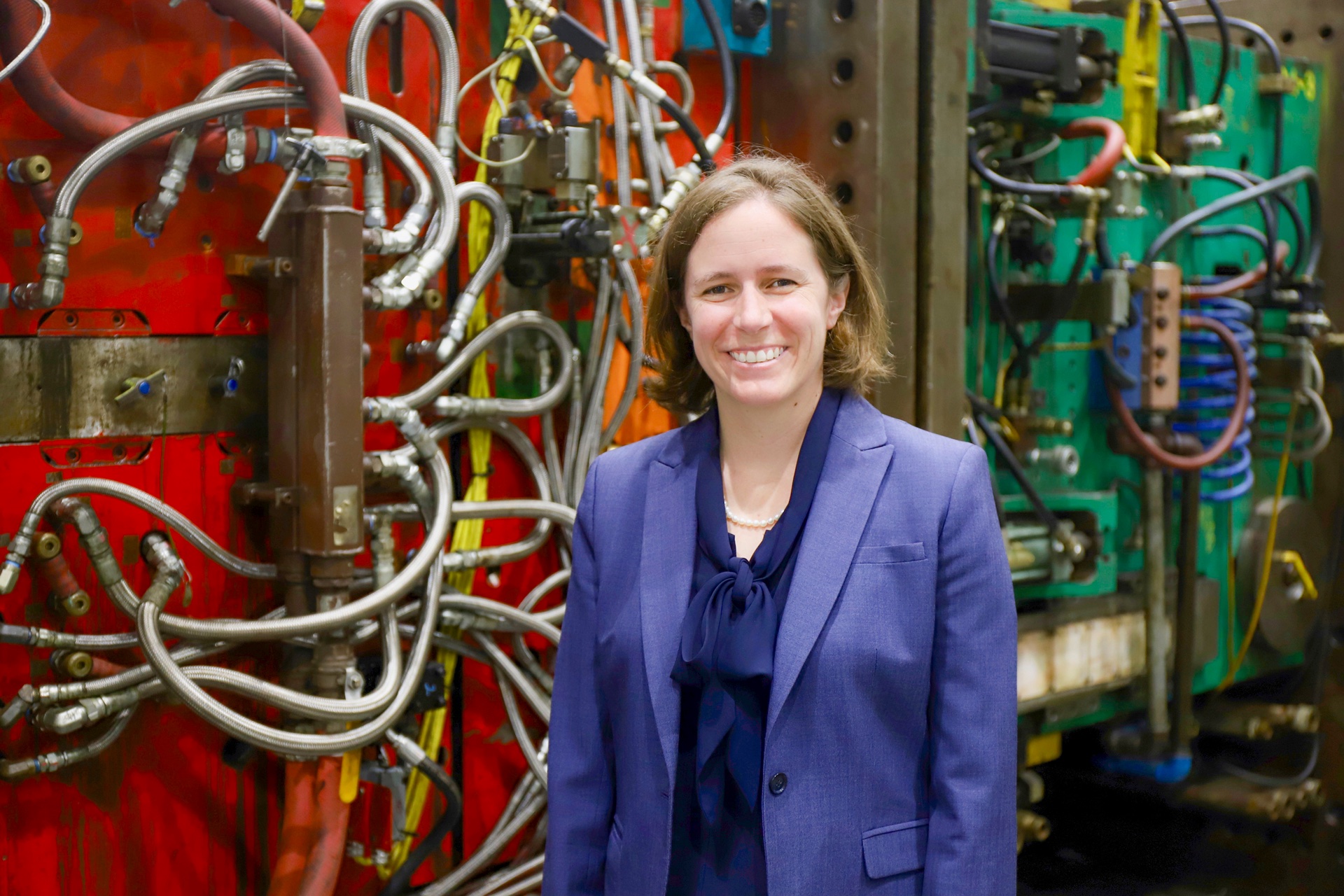

Families who share ownership in a business or enterprise can use their economic power to begin to make a difference.

Photo: Paul Ward Photography.

Chris Herschend, third-generation chairman of Missouri-based Herschend Enterprises, notes that in the post-World War II era when many white entrepreneurs founded their companies, Black Americans could not save or borrow money to start a business. “We had a 70-year head start, and that’s just counting the years since our company’s founding, not the much bigger picture,” Herschend says. (See “The Roots of Inequality.”)

“I’m not saying we should feel bad or give our business away,” says Herschend, whose business is the largest family-owned theme park operator in the United States. “I’m saying, why shouldn’t we harness some of our power to help change this so the story 70 years from now is more balanced?”

In a letter to his family in the summer of 2020, Herschend wrote, “if we turn just a fraction of our strength, energy and economic power and aim it directly at trying to help black Americans ‘catch up’ after hundreds of years of experiences like being denied the GI Bill and far, far worse … could we be an active part of something positive, durable and meaningful far beyond empathy or charity alone?”

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, in 2016 the average wealth of households headed by Black people was $140,000, compared with $901,000 for white-headed households.

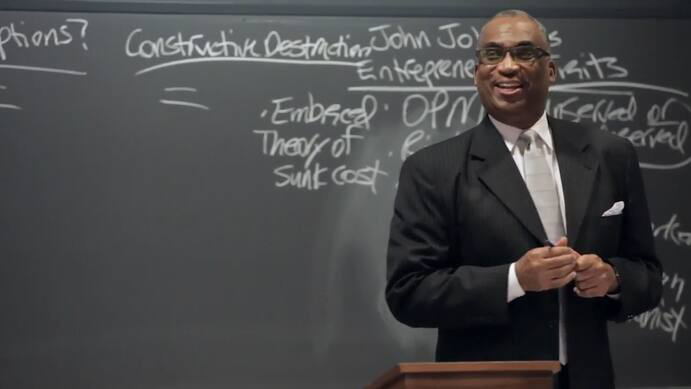

“What we have today is financial apartheid,” says Steven S. Rogers, an independent director of W.S. Darley & Co., a family-owned, Itasca, Ill.-based provider of equipment and supplies for first responders and tactical personnel.

“Whites must educate themselves about the realities of wealth in this country,” says Rogers, author of A Letter to My White Friends and Colleagues: What You Can Do Right Now to Help the Black Community. In a podcast with a similar title, Rogers said, “Unlike our white fellow countrymen, most Black Americans have never experienced the beauty of intergenerational transfer of wealth.”

Black business families’ challenges

The companies on Black Enterprise magazine’s Top 100 list in 2019 generated a combined total of about $25 billion in annual revenues. Compare that with the $110 billion in revenues generated by the largest U.S. privately owned family company, Koch Industries. The top publicly traded family business, Walmart Inc., generated $486 billion in revenues in 2019.

Photo: Ron Witherspoon.

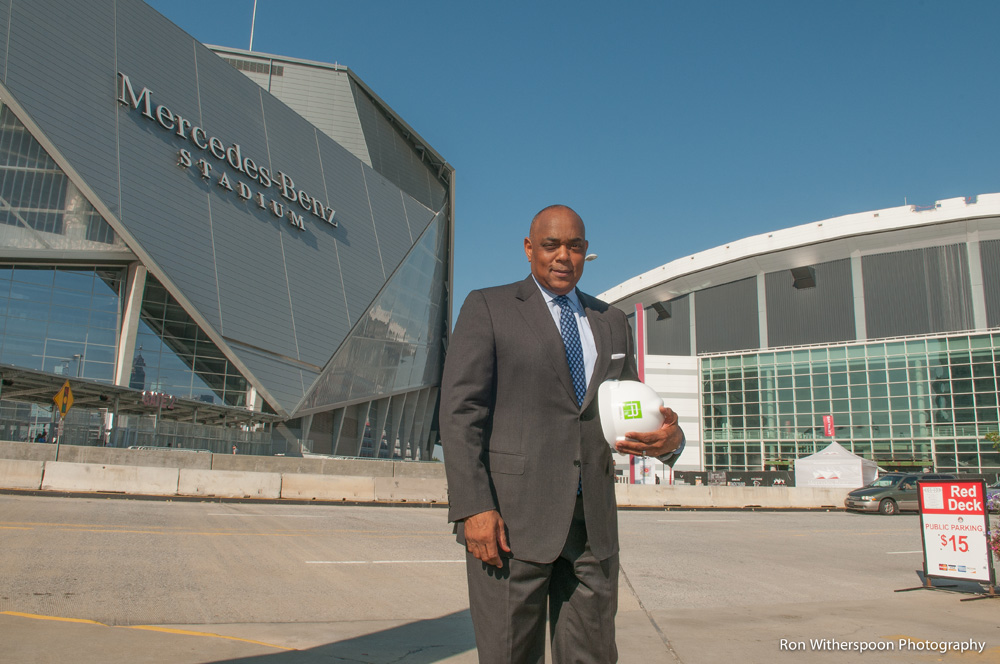

“I absolutely recognize the uniqueness and value of having a Black business of some scale. Black people need to be able to see that level of success to know it’s possible,” says Michael B. Russell, second-generation CEO of Atlanta-based H.J. Russell & Co. The company, founded in 1952, operates in real estate development, construction and property management. The Russell family also owns Concessions International, which operates airport concessions throughout the United States and the Virgin Islands.

“I am sensitive to the fact that we stand as a kind of beacon in an otherwise pretty barren landscape of Black businesses, particularly generational businesses,” Russell says.

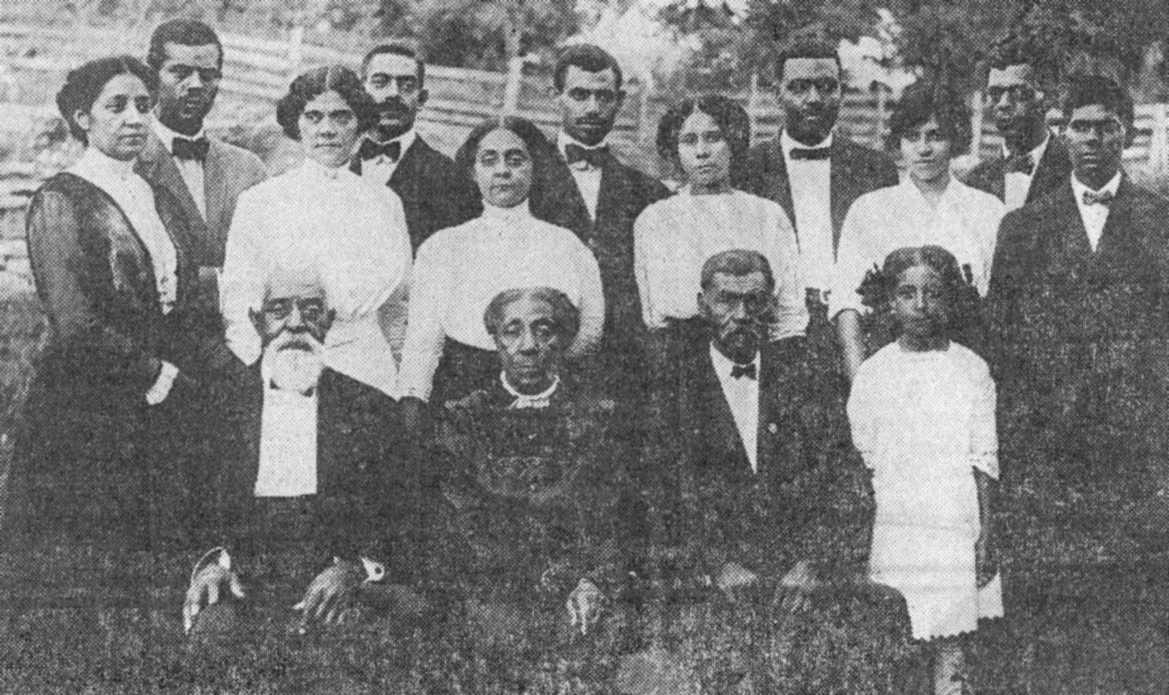

Photo courtesy of the McKissack family.

McKissack & McKissack, the United States’ oldest minority-owned architecture / engineering firm, traces its roots to Moses McKissack, an enslaved man who was brought to America from West Africa in 1790 and learned the building trade from his overseer. Moses’ grandson Moses III moved to Nashville, Tenn., and opened his own construction business in 1905, working with his brother Calvin. In 1921, they were among the first licensed Black architects in the country; barred from college, they studied architecture through correspondence courses and had to lobby for permission to take the exam. When traveling to job sites, they stayed with friends because of racial restrictions at hotels and restaurants.

We’ve got a lot of political differences in our family. So if the entire family, despite those differences, is saying, ‘This is important to us,’ that could be a mountain mover in our spheres of influence.

Today the Nashville firm is headed by Cheryl McKissack Daniel. Her twin sister, Deryl McKissack, founded a Washington, D.C., design/construction firm, also called McKissack & McKissack, in 1990. Each firm has an impressive portfolio of high-profile projects, including stadiums, federal and academic buildings, hotels and hospitals.

Despite their many successes, the McKissacks still encounter hurdles. Deryl McKissack says architects she hired away from a major white-owned company faced extra scrutiny after joining her firm.

“They were the same people who were designing monuments, big office buildings for the Fortune 500, big government facilities,” she says. “All of a sudden, they’re questioned about whether or not they can do something. When they worked for the white company, they weren’t questioned.”

McKissack recently began a 50:50 joint venture with a major architectural firm. One of their clients, when discussing the project, mentioned the partner firm but didn’t credit hers.

Russell praises the creativity of his father, Herman J. Russell Sr., who found ways to succeed “when there was this obvious barrier of racism in the way.”

Herman Russell accumulated the largest portfolio of HUD housing in Georgia in the 1970s and ’80s, when Blacks could not buy real estate. Herman developed a friendship and partnership with a white man, Jim Coclin, who bought the properties on Herman’s behalf.

“They had to keep it moving really quickly, because it was literally dangerous for him and his wife to be buying real estate on behalf of a Black man.”

What can white business families do?

A decision to address systemic racism as a family is powerful, says Herschend. “We’ve got a lot of political differences in our family. So if the entire family, despite those differences, is saying, ‘This is important to us,’ that could be a mountain mover in our spheres of influence.” (See “Opening a Family Discussion.”)

Herschend broached the subject by writing to his family because he felt it important to act immediately rather than initiate a committee process within the governance system.

“I chose to go personal: ‘Here’s how I’m feeling as a person who is personally, politically and spiritually conservative.’ I didn’t position my letter as a call for everybody to change; I just said, ‘I’ve changed.’ ” His thinking had evolved in part through deep conversations with a group of white and Black friends, all men of faith.

The feedback Herschend received from his family “was universally positive and encouraging,” he says.

White-owned family companies can help Blacks create intergenerational wealth by doing business with Black-owned firms.

Rogers notes that Black-owned companies are the largest private employer of Black people in the United States. Hiring these companies provides jobs for Black Americans as well as revenue for the business owners.

He has a list of recommended ways for white business owners to help Black Americans build wealth. (See “Steven Rogers’ Advice to White Business Owners.”) Paul Darley, chairman, CEO and president of W.S. Darley & Co, which provides equipment and supplies to first responders and tactical personnel, quickly took his board member’s suggestion and invested company funds in a Black-owned bank.

Herschend points out that deposits of up to $250,000 in Black-owned banks are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and thus are risk-free.

“Parking some deposit business in Black-owned banks is an easy way to boost Black communities, as these banks are significantly more likely to provide loans and other banking services to Black business owners and homeowners and lower-income communities. These are all benefits my grandmother enjoyed as a customer of a small rural Missouri bank in the 1950s.”

In addition, Elmwood Management, the Herschend family’s investment firm, amended its investment policy to state that “in the ordinary course of our business affairs, we will invest and align Elmwood’s financial and social capital with black managers and/or black-owned businesses or banks where it is wise, mutually beneficial, and prudent to do so.”

“We’re going to try to use some of our economic power to create tailwinds for people who have had headwinds,” says Herschend, who serves as Elmwood’s managing director.

Elmwood, which previously had not invested in first-time funds, recently provided the first check to the first fund offered by a Black private equity general partner.

“Our investment committee felt investing in this fund was consistent with our investment policy statement and the fund cleared all of our due diligence hurdles, which were non-negotiable. We simply felt this manager was going to make some money,” Herschend says. “And we thought, why aren’t we backing him?” The family realized how much harder it was for Black than for white managers to raise first-time fund capital.

Elmwood’s investment committee can find ways to offset or decrease the first-time fund risk at the portfolio level, in the normal course of business. “Without a written statement in our investment policy statement, this was likely to just remain ‘feel-good talk,’ ” Herschend says. “But if nobody invests in a first fund there won’t be a second, and Black general partners need and deserve a second look.”

Confronting history

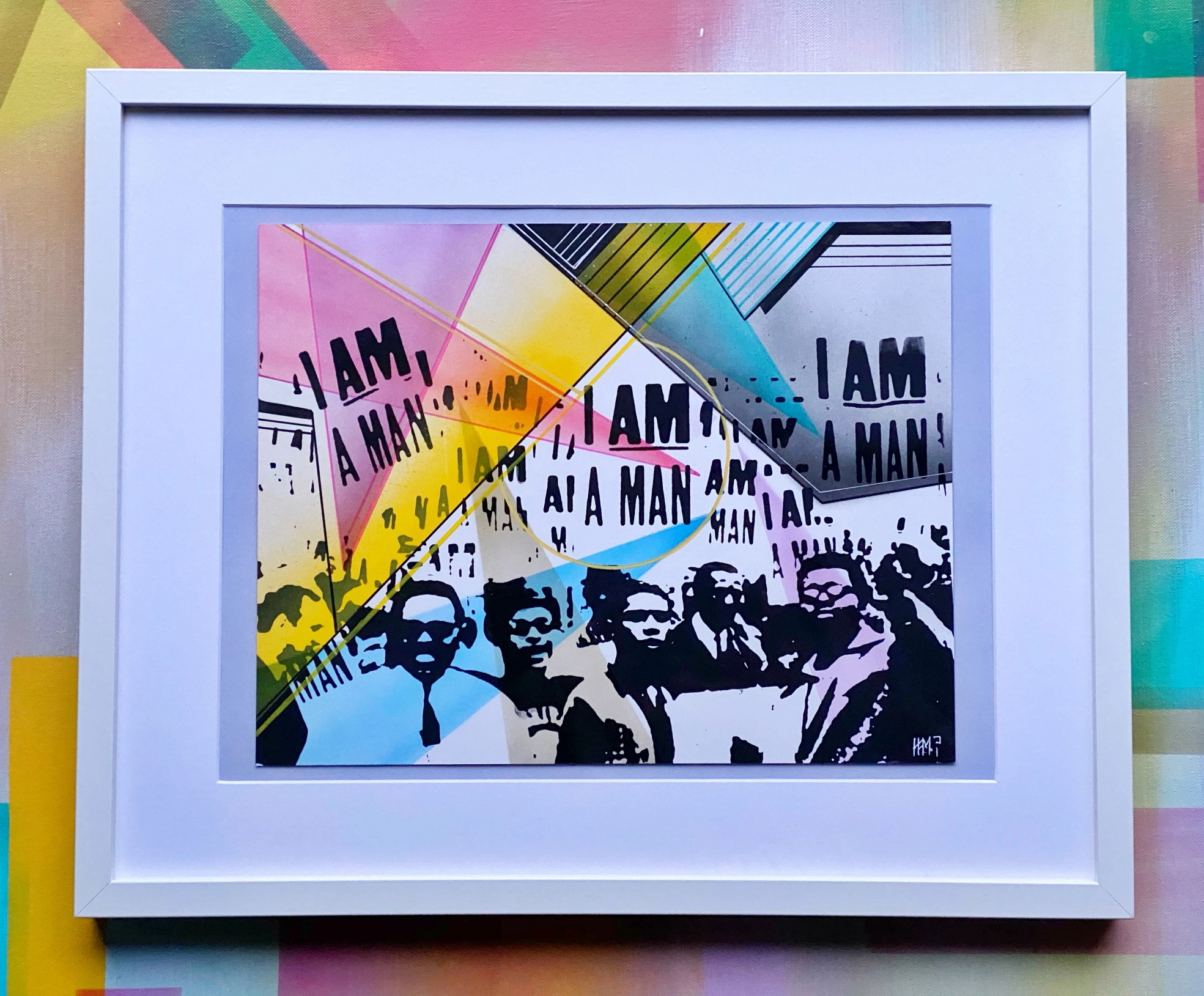

Shirley Plantation’s former laundry building now houses a gift shop. In 2020, Lauren Carter asked Hamilton Glass, a Black artist based in Richmond, Va., to display his work in a gallery space there. He provided pieces inspired by the 1968 Memphis sanitation workers’ strike, in which demonstrators, led by Martin Luther King Jr., protested unsafe working conditions and low pay, holding signs that said, “I Am a Man.”

Photo courtesy of Hamilton Glass.

While passing through the gallery, Carter overheard older white people commenting about the exhibit, “I just don’t understand why something like this would be here.”

“I was thinking, ‘Good, it’s doing what I need it to do,’ ” she recalls. “I’m OK with making some people feel uncomfortable to face something that needs to be faced.”

The Carters’ statement about Floyd’s killing drew a range of reactions, she says.

“We’ve had very positive responses from within our community and around the world. We’ve also had people telling us that we were pandering, and shame on us for not just being proud of the family’s heritage.”

Photo courtesy of Hamilton Glass.

Still others, she reports, have criticized the Carters’ response for not being strong enough. Some have even called for plantation houses to be destroyed.

Charles Carter says of those proposals, “Are you throwing the baby out with the bathwater? We’d lose the history.”

But history was a challenge for Herschend Enterprises, which in July 2020 filed a notice that the company would terminate operations at Georgia’s Stone Mountain Park when its lease ends in 2022. The company has operated attractions at the park since 1998. It does not manage the giant Confederate memorial carving on the site.

According to a statute enacted in 2001 as a compromise when Georgia’s segregation-era flag was changed, “… the memorial to the heroes of the Confederate States of America graven upon the face of Stone Mountain shall never be altered, removed, concealed, or obscured in any fashion.”

Noting that the park has “a great, diverse employee and customer base,” Herschend says the family believed their operations at the park were “bringing light to a dark, difficult place.”

The company discussed with many groups ways to address the racial aspects of the site but was “frustratingly powerless” to effect change, he says. The loss of his company’s rent payments will now force the state to address the memorial, Herschend says.

Acting with intention

Will 2020’s sharp focus on systemic racism lead to sustainable change in the business world? “I’m cautiously optimistic, but I think we’ve still got a long way to go,” Russell says.

“I think the jury is still out on the stickiness of it and in the ability for real change. I think it’s going to be a slow process.”

Meaningful progress won’t occur unless white business owners change the way they operate, Russell says. “You’ve got to step out of your comfort zone. That doesn’t mean it’s more expensive. That doesn’t mean it’s something that can’t work. But you’ve got to be willing to think outside of the normal box, and that’s not easy.

“And you’re going to get resistance. Getting people to change is very difficult, when they have a sense of fear and uncertainty around change.”

Well-publicized efforts will spark broader change, Russell says. “Most people don’t want to lead; they want to follow.

“Hopefully, companies can develop some success and then celebrate it and show how it has made a positive difference.”

Reckoning: Family Businesses Confront Race, Racism and Inclusion

STEVEN ROGERS’ ADVICE TO WHITE BUSINESS OWNERS

The board director suggests ways that white people can use their financial resources to help the Black community.

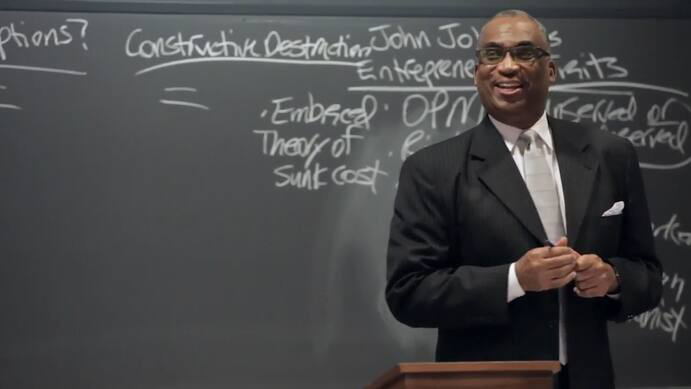

In a podcast entitled “A Letter to My White Friends and Colleagues About What You Can Do,” entrepreneur, board director and business educator Steven S. Rogers suggested actions to help Black Americans build wealth.

Rogers used the figure 8.46% in his podcast in commemoration of 8 minutes and 46 seconds, the amount of time former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin pressed his knee on the neck of George Floyd, according to the Hennepin County Attorney’s initial complaint against Chauvin. Police body camera footage released later showed Chauvin actually had his knee on Floyd’s neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds.

Following are Rogers’ recommendations, excerpted from his podcast.

1. “Commit to spend at least 8.46% of your annual budget buying products or services from Black-owned businesses. The 2 million Black-owned businesses in the country are the largest private employers of Black people.”

2. “Deposit at least 8.46% of your savings into Black-owned banks or credit unions. Remember, accounts of up to $250,000 are fully guaranteed by the federal government through the FDIC. Therefore, this action is completely risk-free. Black banks provide mortgages, auto loans and business loans to the black community. We need you to open an account. Leave it there for three to five years. Black banks have fared poorly because most of their depositors are poverty-stricken people who make small deposits and quick withdrawals. Therefore, your large deposit that remains there for multiple years will help the Black community.”

3. “Donate meaningful dollars over several years to Historically Black Colleges and Universities, also known as HBCUs. There are 300,000 Black students matriculating at HBCUs. The average endowment is a mere $12 million. Over 60% of the students are first-generation college students. Our HBCUs need help. They have been an integral part of the American education system.”

4. “Put at least 8.46% of your investments with Black-owned financial services companies. Those businesses include Black mutual funds, investment banks, compliance firms and private equity firms.”

5. “My final recommendation is the boldest and most transformative for the Black community and for the country. Black Americans make up 12% of the country's population, but only have 1% of its wealth. In 1864, one year after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, the newly free Black men and women had half a percent of the country's wealth. Over the next 156 years, the Black wealth has increased only a half a percent. Therefore, I believe the only way that the Black community can exit from the category of being a poor race is through reparations. This is the means by which the wealth difference between Blacks and whites can be eliminated. So please support reparations to Black Americans.”

“I encourage you to do at least two of the items that I’ve mentioned above and, if possible, do all of them.”

For further reading:

Steven S. Rogers, A Letter to My White Business Friends and Colleagues: What You Can Do Right Now to Help the Black Community.

Reckoning: Family Businesses Confront Race, Racism and Inclusion

ACHIEVING REAL DIVERSITY, EQUITY AND INCLUSION IN YOUR FAMILY BUSINESS

The keys to successful DEI strategies: Committed leadership, a clear vision and measurable results.

In response to nationwide protests following the police killing of George Floyd, companies issued statements condemning racism and expressing a commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion. But Black Americans are skeptical that white-owned businesses will back up these words with meaningful, lasting changes.

Diversity efforts “are only as effective as they are measured and people are held accountable,” says Deryl McKissack, CEO of Washington, D.C.-based architecture and engineering firm McKissack & McKissack, who traces her roots in the industry to an enslaved ancestor.

When the going gets tough, that's when leadership has to double down.

“The efforts that I am aware of have been statements, and I need to see something more tangible,” says Steven S. Rogers, an independent director of W.S. Darley & Co., a family-owned provider of equipment and supplies for first responders and tactical personnel.

“Being anti-racist to me in 2021 means sharing wealth with Black people,” Rogers says. “Simply saying, ‘I am anti-racist’ is just a nice-sounding jingle.”

Setting the tone at the top

An organization’s top leadership must take the primary role in advancing diversity, says Mary-Frances Winters, president and CEO of The Winters Group, which helps business leaders develop diversity and inclusion strategies.

“It’s not delegated to the H.R. department or someplace else. Leadership talks about it as a part of their overall business strategy. It’s embedded as a part of who the organization is — what we stand for, what we’re about. The leader doesn’t have any reservations about sharing his or her values and what’s expected.”

Companies that are serious about diversity must codify it in their values, Winters says. “When people in an organization have a poor attitude about it, then the leader of that organization needs to go back to the values.”

Business owners must get past their discomfort with these issues, Winters says. “Going to the dentist is uncomfortable. Learning golf is uncomfortable. There are a lot of things in life that are uncomfortable, but we still do them.

“When the going gets tough, that's when leadership has to double down.”

Opening the boardroom door

Having Black representation on your board will help your family company achieve meaningful progress in diversity, equity and inclusion, Black business leaders say.

“It’s time for people to say, very explicitly, ‘I want Black Americans on my board of directors,’“ Rogers told attendees at the Private Company Governance Summit in 2020. “When we use other words — ‘minority,’ ‘people of color’ — historically what it tends to result in is the dilution of Black people. I am very emphatic that it be Black Americans right now.’ ”

Black board members can help make connections with Black-owned companies that would excel as contractors or business partners, says McKissack.

McKissack’s firm was the project manager for MGM National Harbor, a casino resort in Prince George’s County, Md. MGM’s Black directors advocated for minority leadership on the project, says McKissack.

Black directors “can help facilitate the discussion and then help with accountability” on diversity, equality and inclusion, McKissack says. They can help white business owners understand these issues from a Black person’s perspective, she adds.

Some companies have adopted a version of the “Rooney Rule,” developed by Pittsburgh Steelers owner Dan Rooney, who pushed for a policy requiring National Football League teams to interview minority candidates for coaching positions.

Because private company directors tend to be long-tenured, Rogers recommends creating an additional board seat to get a Black director in the role within 12 months. “When you need something done to address a special problem, you might do something special,” he advised Private Company Governance Summit participants.

Rogers urges business owners to look deeper into the Black American talent pool rather than bringing aboard someone who already serves on multiple boards.

“If you get exposed to someone who is Black who you believe has the ability to be an outstanding director, make that move and engage them,” he said at the governance summit.

Rogers’ own bio offers examples of this principle in action. He was 39 years old — younger than most board directors — when William Perez, then CEO of S.C. Johnson & Son, invited him to join that company’s board. Rogers had worked for Bain and Company and then owned and ran his two manufacturing firms and a retail store. Although Rogers hadn’t worked in a corporate C-suite, Perez realized his perspective would be valuable on the S.C. Johnson board. Rogers was a director of the giant consumer-products company for 23 years.

After selling his companies, Rogers joined the faculty of Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management and later was a faculty member at Harvard Business School. Paul Darley, chairman, CEO and president of W.S. Darley, was a student in Rogers’ entrepreneurial finance class at Kellogg. Rogers notes with a laugh that Darley asked him to join his family company’s board early in the semester. “I said, ‘Why don’t you wait until I finish teaching you before you offer me graft?’ ” he jokes.

Getting started

Diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) must be viewed as an integral part of the company, equivalent to finance or marketing, Winters says. “It needs to be integrated and embedded into the ongoing work of an organization in order for it to have any traction or sustainability. You look at it as part of the operation. It’s part of what you need to do in order to operate successfully.”

The work should start with establishment of a vision, Winters says. “What are you trying to do? What do you want your organization to look like when you have diversity, equity and inclusion?”

The next step, Winters says, is to conduct an audit to assess how far the company currently is from your vision. “What’s the gap, and how are we going to close that gap?” The company should aim to establish a culture that embraces diversity, not merely to check a box, she stresses. “What environment should we have to ensure the success of individuals who have been historically excluded?”

Photo: Ron Witherspoon.

Winters advises companies to distribute mission and vision statements that explain why the organization is undertaking the effort and how it can benefit everyone in the organization. The goal should be “to create an environment that works for all,” she says.

“Inclusion truly should be inclusion,” Winters says. “And so whatever the dominant group is in the organization, they should see themselves in this initiative, as well. They should see that there’s a role for them to play.”

In June 2020, Michael B. Russell, second-generation CEO of Atlanta-based H.J. Russell & Co., a real estate development, construction and property management firm, distributed a social justice/diversity statement to employees.

The George Floyd protests “made me think about how within our organization, we can do a better job of diversity,” Russell says. “Just because we’re a Black-owned company doesn’t mean we’re best in class in diversity.”

To inform employees of changes, Winters suggests a town-hall format that includes a Q&A component. “An important thing that will lead to success is being very transparent,” she says.

Hiring, promoting and mentoring Black employees

Simply hiring Black employees isn’t enough; companies should provide mentoring to help them earn promotions and move up the ladder, Rogers says. He quotes Harvard Business School professor Frances Frei, who focuses on helping leaders remove “pebbles” — obstacles to performance — which are often perceived as “boulders.”

“If a person has to walk on pebbles barefooted, it becomes an impediment, and then they leave,” Rogers says.

At the Cascade Engineering Family of Companies, a Grand Rapids, Mich.-based global manufacturing company specializing in large-part plastic injection molding, executive vice president Kenyatta Brame, who is African American, serves on the three-person leadership team along with second-generation president and CEO Christina Keller and CFO Janice Oshinski. Keller says Brame identified the company’s first Black director, Bill Manns, who joined the board in January 2021.

Manns, president and CEO of Kalamazoo, Mich.-based Bronson Healthcare, is a community leader who can help the company achieve its strategic goal of being an employer of choice, Keller says.

Brame’s department measures workforce diversity, pay equity and employee satisfaction. Recent employee survey data have shown a marked increase in satisfaction ratings for minority employees, Keller says.

“It’s on us to be connected to people and empowering,” she says.

One of the things that we say is, ‘We’re not trying to change your beliefs. We’re just establishing the behaviors that are acceptable and not acceptable within our organization.’

Cheryl McKissack Daniel, twin sister of Deryl McKissack and CEO of the family’s original Nashville, Tenn.-based firm, also called McKissack & McKissack, says a white family business owner can make a difference by mentoring a Black person and teaching them about business — “even just one, because that one will hire people who look like them.

“Help put someone in business so that they can control their own destiny.”

In 2019, McKissack Daniel and consulting engineer John Rice formed Legacy Engineers, an engineering consulting firm, “for the sole purpose of giving Black and Hispanic engineers an alternative firm to go to where there would be no glass ceilings.” Their ultimate goal is to turn the company over to the employees. “We’re training them to be owners,” she says.

Some of these engineers “have been fighting just to be equal,” she says. “They don’t have the same training as their white counterparts. We have to train them.”

H.J. Russell & Co. has established the Russell Innovation Center for Entrepreneurs (RICE), a non-profit business generator that will provides connections and resources for Black fledgling entrepreneurs and small-business owners. RICE will offer a curriculum to help the entrepreneurs develop, execute, accelerate and scale their ideas.

RICE, housed in H.J. Russell’s former office building, was developed as a tribute to the company’s late founder, Herman J. Russell Sr. “My dad was an incredible entrepreneur,” Michael Russell says. “He would certainly be pleased to see that this center is building entrepreneurship.” Russell’s brother, H. Jerome Russell Jr., chairs RICE’s board.

Setting strategic priorities

Companies committed to DEI should link those values to a key strategic priority, says Keller. “It’s definitely important to have that commitment and that strategy up front,” Keller says. “Those are the things that make it stick.”

At Cascade, a Certified B Corporation, diversity is tied to the company’s strategic goal of being an employer of choice. The company developed an anti-racism policy in the 2000s. The policy states, in part, “Cascade Engineering defines being an anti-racism organization as creating an environment where all employees regardless of race or the color of their skin know they are valued.”

“As a manufacturing organization, we've got a diversity of people from the office to the production floor, with people coming from very difficult backgrounds on both sides of the color spectrum,” Keller says. For some Cascade employees, their workplace is the most diverse place they have ever encountered, she notes.

“One of the things that we say is, ‘We’re not trying to change your beliefs. We’re just establishing the behaviors that are acceptable and not acceptable within our organization.’ ”

Cascade has a Welfare to Career program, designed to help people leave welfare and begin a meaningful career. The company also hires returning citizens (people who were previously incarcerated).

Cascade’s pay-for-contributions program creates clear pay levels and career paths, Keller says. Training and development opportunities, apprenticeship programs and other support systems help entry-level operators advance along technical or administrative career paths.

The company joined with other local area manufacturers to form The Source, a non-profit employee support organization. Through The Source, on-site social workers can assist with personal issues such as tax preparation, financial counseling, credit score improvement and transportation. In partnership with The Source, Cascade created a program to provide financial assistance and support to employees buying their first home, as well as tuition scholarships to local colleges.

Founder and chairman Fred Keller (Christina’s father) led the effort to make Cascade an anti-racist company. At Cascade, the term “anti-racist” means that the organization not only condemns racism but also actively fights it.

Everyone in a leadership role at Cascade must attend sessions offered by the Institute for Healing Racism, a program of the Grand Rapids Area Chamber of Commerce. The institute provides a safe space for frank discussions among community members from diverse backgrounds. Participants learn tactics for fighting racism in their workplaces, personal lives and communities.

All Cascade employees participate in Diversity Theater, in which actors portray people in real-world workplace scenarios addressing race, gender, sexual orientation and other types of diversity. “We capture those stories with H.R., and then actors act them out,” Christina Keller says. The discussion that follows builds awareness and stresses the importance of treating others with dignity and respect. “By talking about it, we are able to avoid [disrespectful situations] happening in the future,” Keller says.

The company’s Diversity Coordinating Council plans activities like food-centered celebrations of different ethnic backgrounds. The communications department produces an annual Diversity Calendar.

There have been instances of pushback, Keller acknowledges. Some employees did not pick up their copy of the 2021 Diversity Calendar, whose theme, “Lift Every Voice,” focused on protests demanding justice and equal treatment under the law.

One employee was unwilling to take a moment of silence after the death of George Floyd. “That was a very interesting thing to work through,” Keller says. “We just reinforced with them that this wasn’t a political statement, it was just taking some time to reflect or pause. I think they were OK with that, and we moved through it.”

At McKissack & McKissack, “We sometimes talk about how in the construction industry, combating racism and sexism is important to safety,” Deryl McKissack says. “In construction, there are a lot of things we have to do that require a team. You have to look out for the next person. And if you don’t, then someone can really get hurt.”

Sometimes a family business will move forward on DEI before the family stakeholders have reached agreement on their values around the issue, says Ashley Blanchard, philanthropy practice leader and a consultant at Lansberg Gersick & Associates, a family business advisory firm.

“I’ve definitely seen that happen: A company with family leadership takes some bold action on diversity, equity and inclusion — makes a public statement, contributes funding, makes internal policy changes or commitments around hiring practices. And that spurs the family to step back and say, ‘Hey, wait a minute, we’re now kind of leading on this topic, and we realize there's a lot of work we have to do.’ And that can actually be totally effective.

“I think if you wait till everybody’s hit some magic level of perfection in their diversity, equity and inclusion journey, it’s going to be a long time coming.

“Taking some action — that may feel uncomfortable to some and may feel too slow to others — is often actually what catalyzes families.”

Reckoning: Family Businesses Confront Race, Racism and Inclusion

ADDRESSING ENSLAVEMENT IN YOUR FAMILY'S PAST

Confronting painful history can lead to healing.

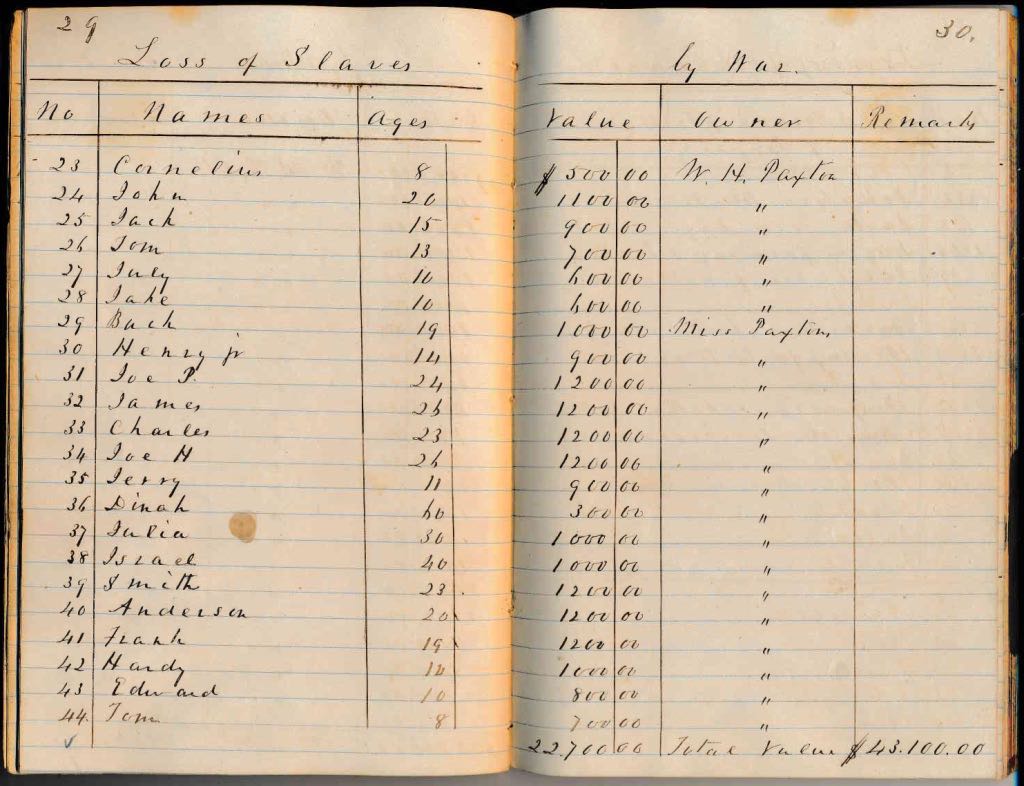

Photo courtesy of Lotte Lieb Dula.

Lotte Lieb Dula had a “deeply disturbing aha moment” in 2018, while going through boxes that had been stored away for generations in the 6,000-square-foot San Diego home where she grew up. Underneath a layer of daguerreotype photos, she found a “beautifully penned book of records.”

Dula, who had just retired from her career as a financial strategist, at first found it interesting that she might have inherited her financial skills from an ancestor. Paging through the ledger, she found an inventory of items lost during the Civil War. Beginning on page 27, under the heading “Slaves Lost by War” was a list of names, ages and values.

Dula knew her mother’s forebears came from the South. “But it had never occurred to me that my family had a direct relationship with enslaving other people.”

Her great-great-great-grandfather, Elisha Paxton, owned a plantation near Lexington, Va. His sons, including her great-great-grandfather, William Hays Paxton, whose record book she had found, became attorneys and ran plantations on the side. Although Dula’s ancestors did not transfer a business to succeeding generations, her emotions upon discovering she benefited from their wealth offer insights for enterprising family members whose ties to enslavement have been hidden.

Uncomfortable episodes in the history of a family or company should be acknowledged rather than buried, says Mark Speltz, senior historian and vice president at the Wells Fargo Family & Business History Center.

“Open communication is critical to understanding challenges and putting them in proper context. It can lead to healing,” Speltz says. “If you seek to discuss it, then you can move forward. Each family has to figure out how to do that.

“Sometimes people figure if they don’t talk about challenging elements of family and business histories, the details will somehow go away, but that’s no longer true” because information is now readily available online, Speltz points out.

In business families, the stories that get passed down tend to focus on entrepreneurial ingenuity, but NextGens want a fuller picture. “Sometimes that might mean there are details that they come to on their own, or they put two and two together and figure it out,” Speltz says. “If they encounter something that they’re uncomfortable with, well, other people probably are going to be uncomfortable with it, too.”

Families should approach these conversations with respect for different viewpoints, Speltz advises. To establish a productive framework for the discussions, he recommends that family members respect the past, focus on learning from it and align around the desire to move forward as a family.

“All the history work we do with families and businesses establishes what I think of as a solid foundation. You can then have future discussions about values, vision, philanthropic goals. It can lead to important legacy work.

“The first step in navigating historical challenges is to understand them in context — what they meant then and what they mean now,” Speltz says.

It’s easier to move forward when the family has discussed their history together, he says. “That's the solid foundation that you can jump off from, with a deeper understanding. Then you’re all working from that same spot.”

Some members of the DeWolf family, descendants of the largest slave-trading dynasty in U.S. history, confronted their history by taking a journey together.

Photo courtesy of Tom DeWolf.

Photo courtesy of Tom DeWolf.

A family explores its slave-trading history

In 2001, 10 members of the DeWolf family retraced the “Triangle Trade” route from their ancestral hometown of Bristol, R.I., to the coast of Ghana and then to the ruins of a sugar plantation in Cuba, one of several owned by their ancestors. Their trip, a step they took to learn and heal as a family, was recorded in a documentary, Traces of the Trade: A Story from the Deep North. The film, released in 2008, aired on the PBS series P.O.V.

Photo by Elly Hale.

Filmmaker Katrina Browne, a DeWolf family member, invited 200 known descendants to participate. The 10 who had the desire and the resources to join the trip ranged in age from 32 to 71. The group included sibling pairs and a father and son as well as sixth and seventh cousins who had never met before. The film offers an intimate view of their evolving family dynamics.

The itinerary centered on the legacy of second-generation family member James DeWolf (1764-1837), whose ships brought tens of thousands of enslaved Africans to the United States. DeWolf served as speaker of the Rhode Island House of Representatives and as a U.S. senator.

The DeWolfs made rum in their New England distillery and traded it in West Africa for captured Africans, whom they brought to Cuba and other Caribbean ports as well as to Southern states. Molasses from the family’s Cuban sugar plantations was used to make the rum. The sprawling family enterprise also included an auction house, an insurance company, a bank and coffee plantations. Their slave-trafficking dynasty lasted for three generations.

James DeWolf Perry VI knew very little about the ancestor for whom he was named. His grandfather knew James DeWolf had been a merchant and that he “tried his hand at the slave trade,” Perry says.

Photo courtesy of Tom DeWolf.

“When you say it that way, it sounds like he had tried it and abandoned it. And of course, it turns out that the reality couldn't have been any different.”

Perry’s distant cousin Thomas Norman DeWolf had known nothing about his ancestors. The film depicts DeWolf’s visceral reaction to a walk through the dungeon of Cape Coast Castle in Ghana, where captured Africans were held before being forced onto ships bound for the Americas. DeWolf wrote a memoir of the trip, Inheriting the Trade.

About 40 family members who didn’t go on the trip joined the travelers for a church service in Rhode Island filmed as the ending of the documentary.

I have followed this discussion for 25 years. And now, for the first time, I have the sense that more people are really willing to engage this history.

Photo courtesy of Tom DeWolf.

While 21st-century Americans are not responsible for the actions of their long-dead ancestors, “what they are responsible for is to acknowledge this history and to engage with this history,” says Sven Beckert, a Harvard University historian and coeditor with Seth Rockman of Slavery’s Capitalism: A New History of American Economic Development.

“I think acknowledging what has occurred and apologizing for it not only helps Black people, but frees [enslavers’ descendants] of the pain. We already know it, so just tell us,” says Cheryl McKissack Daniel, CEO of Nashville, Tenn.-based architecture / engineering firm McKissack & McKissack, who traces her family’s roots in the building industry to an enslaved ancestor.

“I try to have empathy and put myself in a white person's shoes,” McKissack Daniel says. “It’s embarrassing. It hurts. And you don’t want it to be real.”

Healing together

Several members of the DeWolf family have become active in a national organization founded in 2006 called Coming to the Table (CTTT), which brings people together to work toward racial reconciliation.

Some CTTT members are descendants of enslavers, some are descendants of the enslaved and many are descendants of both slaveholders and slaves. Other members have no known family connection to slavery but are drawn to the mission. More and more have expressed interest since the killing of George Floyd, says Tom DeWolf, CTTT’s program comanager.

“People of European descent are learning things that they’d never known before, and having to reckon with their knowledge,” DeWolf says. Open conversations between descendants of enslavers and descendants of enslaved Africans helps everyone to heal, CTTT members say. The outcome of these discussions is similar to the positive results many business families report from candid family conversations.

The group’s approach to “deep dialogue” is centered on mutually agreed-upon principles that guide how participants treat each other so everyone feels safe enough to speak honestly.

Making amends through reparations

Within 24 hours after discovering that her ancestors were enslavers, Dula had concluded, “I’ve got a debt to pay.”

Dula realized enslavement had helped fund the education of generations of professionals in her family. “My forebears basically cheated people out of fair pay and then used that to our advantage as a family, and I was reaping the benefits. I owed back pay, essentially.”

Since uncovering her family’s hidden history, Dula has made personal reparations. She’s also created an internet portal, Reparations4Slavery.com, which provides resources for white families on personal and societal reparations. Another resource is the downloadable Reparations Guide developed by CTTT’s Reparations Working Group.

Dula has publicly announced her commitment to pay $500,000 in personal reparations. She began by creating a scholarship through the United Negro College Fund. Because her family tree includes attorneys, doctors and statesmen, the scholarship supports Black students in law, medicine or political science.

“What I advise people to do is create a plan of repair based on your family’s specific trajectory in this country,” Dula says.

“I have followed this discussion for 25 years,” says Beckert. “And now, for the first time, I have the sense that more people are really willing to engage this history. And I think that's a very positive development.”

Ashley Blanchard, philanthropy practice leader and a consultant at Lansberg Gersick & Associates, a family business advisory firm, says reparations are being discussed in some family foundations.

“Certainly, in some of the more progressive family philanthropy networks, there are conversations around philanthropy as reparations and the role of philanthropy in supporting a movement for reparations,” Blanchard says.

“When you have family members — NextGen, generally — talking about reparations, in some cases that causes some family members to shut down. In other cases, it’s a wake-up call.”

When Dula told her sister that she’d be making reparations instead of leaving money to her nephews, she received an “amazing” response.

“She said, ‘You are going to restore honor to our family line, and I really appreciate that. Don’t worry for a second about my kids; they’re going to be fine. They will make their way in the world. And with what you’re doing, they can make their way in a way that is honorable.’ ”